This paper summarizes the progress on the EU Capital Markets Union in recent years (it was demure!); the next steps necessary as identified by Eurogroup, ECB, the Letta and Draghi Report & Draghi Report; and why all of this matter for the European Central Bank and monetary policy. Despite all the big words, the progress on the CMU in the past decade was … demure! (this trending word actually means „reserved, modest”, exactly the type of progress the CMU has had). The EU should have proven to be the right landscape for a large, well-integrated single capital market. Instead, fragmentation across national borders hinders the efficient usage of capital and leads to costliers funding for firms and underutilisation of EU private savings. I document the huge gap between EU & US capital markets across many dimensions: size of equity markets, households participation, firms’ financing structure, role of institutional investors & venture capital.

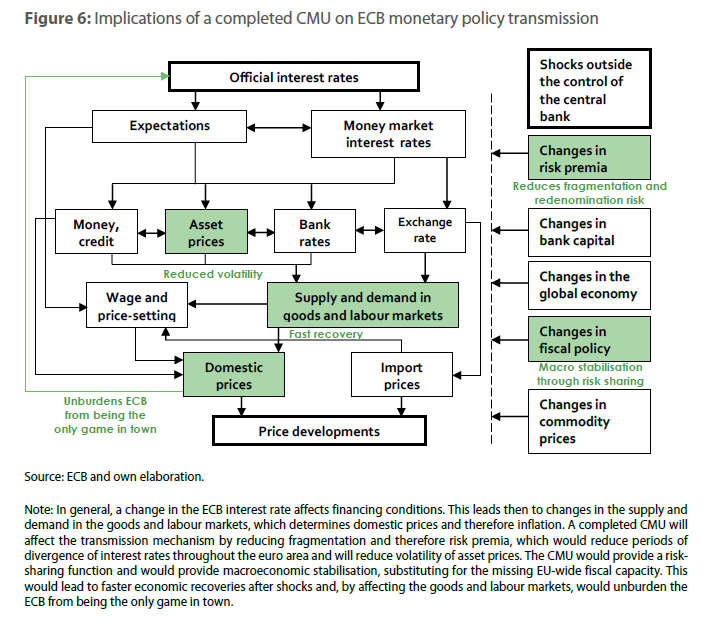

Why does that matter for the ECB? The unfinished nature of the CMU has direct relevance for the ECB by affecting financing conditions in Member States and eroding the risk-sharing ability of the EMU, imposing a higher burden on the ECB to act as “the only game in town”. The current EU financing structure contributes to diverging financing conditions in Member States. The bank-dominated landscape in the EU might impede economic recovery through subdued credit growth following downturns and negative financial stability implications. Most importantly, the lack of sufficient risk-sharing in the EMU contributes to a high burden on the ECB to be the only game in town in terms of macroeconomic stabilisation, as long as there is no common fiscal budget as a form of risk-sharing. Famously, the euro is like a bumblebee – according to nature it should not be able “to fly” (function), yet it does. Completing the CMU can help the euro “fly” and achieve “soft landing” bc it affects ECB transmission and unburdens it from the role of “only game in town”.

The study also includes a comparison of recent statements by the Eurogroup, the ECB Governing Council and the Letta & Draghi Report on what to do next for CMU. There are many steps which are shared by all four and the EU should move on them fast! One cannot oversee that the statements by the ECB & Eurogroup largely ignore one crucial element of a true CMU: the creation of a permanent EU safe asset. Ignoring the importance of a safe asset is all the more regretful in the statements of the Eurogroup and the ECB Governing Council given the strong performance of NextGenEU bond issuances since their introduction.

Given all of the above, I conclude with 3 points. 1. A “Kantian shift” in thinking about CMU is essential – this project is relevant for EU citizens in finding a better use of their savings to face the challenges the EU is facing. New Commission portfolio for Savings & Investment Union is a step in this direction by EU Comm. 2. There are concrete steps on which we agree on 3. Yet there continue to be 27 national views on CMU – they need to converge to achieve a unified capital market.

(The research was prepared as part of the Bulgarian National Bank annual scholarship for young researchers)

Policy related

„Uncertainty in the Euro Area during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic“ with Stefan Schiman, Study for the European Parliament’s Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs; in

„The role of fiscal rules in relation with the green economy“ with Margit Schratzenstaller, Study for the European Parliament’s Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs

Pekanov, A., “The New View on Fiscal Policy and its Implications for the European Monetary Union”, WIFO Working Papers, (562), 2018. [slides]