Overview of various reform proposals (selected proposals from recent years)

Introduce Nominal Expenditure Growth Rule (growth ceiling for annual adjusted nominal expenditure growth)

Structural deficit rule for the medium-term target through a multi-purpose adjustment account (“memory” in the fiscal rule to achieve budget close to balance over the business cycle)

Pre-specified debt ratio as its long-term limit achieved with a debt-correction factor (“memory” in the fiscal rule to compensate for previous excessive spending)

Darvas, Martin and Ragot (2018)

Nominal Expenditure Growth Rule for the medium-term, consistent with a given debt-target

No compensation for previous excessive spending

Discretion on the type of expenditure

National Fiscal Councils decide on the annual target for the expenditure ceiling

Debt-rule based on a medium-term (e.g. 5 years-ahead) country specific target of reduction on the debt-to-GDP target, proposed by the government

Revision of the Stability and Growth Pact towards an expenditure growth rule (without annual progression towards the long-term target of 60%), but retaining the 3% limit for nominal deficit and abandoning targets for the structural balance.

Annual target for expenditure growth should depend on medium-term projection of nominal potential growth and a judgement on the convergence towards long-term debt ratio

National Fiscal Councils prepare projections for potential growth over the medium term

Introduce a Golden Rule: public investment should be financed with debt

A PAYGO rule for current expenditures: increases in current spending or tax cuts to be paid for on a five-year forward basis

Independent fiscal council must evaluate fiscal proposals before adoption

Mandatory annual spending review, performed by independent national fiscal council

Simple Long-Term Debt Target

Simple Rule for Net Spending Growth

Differentiate adjustment rates for public debt reduction between countries

Giavazzi, Guerrieri, Lorenzoni and Weymuller (2021)

A two-pillar proposal to revise existing fiscal rules as well as introducing a new European Debt Agency to absorb part of the pandemic-related debt

Fiscal rules adjusted to limit the maximum growth rate of government primary spending

Fiscal adjustment should be set as an annual path to reduce debt, where debt is split into a part that us reduced faster and debt that can be reduced at a slower pace (COVID-19 debt and debt for EU priorities such as the Green transition)

Move part of national debt to a newly created European Debt Management Agency, with the aim of reducing debt costs for the whole Union and helping the operations of the ECB in debt markets

Francová, Hitaj, Goossen, Kraemer, Lenarčič and Palaiodimos (2021)

A two-pillar approach that utilises a 3% fiscal deficit ceiling and a 100% general government debt reference value that incorporates an expenditure rule

Expenditure ceilings that track trend growth would replace existing medium-term objectives expressed in structural balance terms.

Government expenditure growth should not be higher than the potential or trend growth rate

Martin, Pisani-Ferry and Ragot (2021)

Remove the uniform numerical thresholds for the debt (60% of GDP) and the deficit (3% of GDP)

Each country sets a medium-term debt target based on an assessment by the domestic IFIs and then endorsed by the EU

After a debt target has been set, an expenditure rule will guide the path for primary nominal expenditures towards this debt target.

Blanchard, Leandro and Zettelmeyer 2021

Do not use fiscal rules and deficit and debt thresholds – instead introduce country-specific debt sustainability analysis (DSA), a form of standard for different countries and accompanying debt reduction plans tailored to each Member State

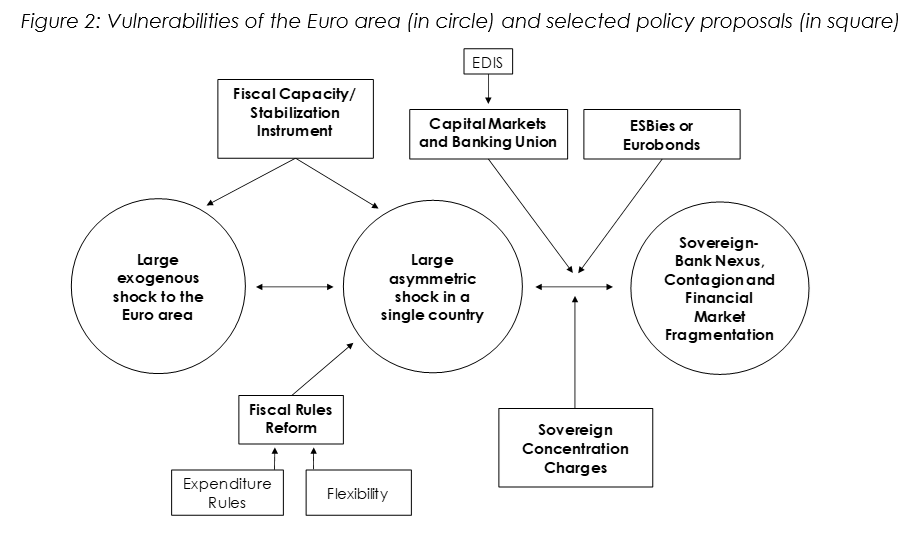

Euro area reform has been at the center of much needed discussions throughout recent years. The Euro area crisis has made it clear that significant vulnerabilities still exist in the current architecture of the European Monetary Union. This has opened an intellectual and policy debate on how to make the EMU more crisis-resilient and whether the Euro area requires more risk-sharing or more market discipline to this end. Along these lines, numerous proposals have been presented by institutions and academics such as the introduction of a common fiscal policy instrument, possible reforms of the current fiscal rules, the creation of a Euro area safe asset to break the sovereign-bank nexus and a common European Deposit Insurance Scheme. This policy brief summarizes the discussions and policy proposals for EMU reform of recent years. After intensive debates, the necessary consensus was not found and no significant breakthrough on EMU reform has been achieved to reinforce the ability of the monetary union to withstand future crises. These intellectual discussions have however laid the groundwork for finding the right answers at the particular moment in the future when political compromises will make it feasible to strengthen the Euro area in a healthy and efficient manner.

WIFO Monatsbericht, April 2022

The EU economy was on the road to recovery in 2021, but continued to be shaped by high uncertainty about the further development of the COVID-19 pandemic. Key to the economic recovery was expansionary monetary and fiscal policy in the EU and euro area, which was characterised by high inflation rates toward the end of 2021. This paper discusses three main themes of EU economic policy in 2021-22: the monetary policy strategy review, the future of fiscal rules and the implementation of the NextGenerationEU instrument. The recently adjusted monetary policy strategies of the European Central Bank as well as the Federal Reserve tolerate higher inflation rates in the short term, but remain oriented toward the 2 percent inflation target in the medium term. Selected proposals for reforming EU fiscal rules take as their starting point the significant increase in member countries‘ indebtedness while pointing to the secular reduction in equilibrium interest rates that reduces the debt burden. Finally, the paper discusses the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), the centerpiece of NextGenerationEU. The RRF is already in the implementation phase and is expected to lead to important investments and reforms in the coming years.

EU Heads of States (Photographic Archive of the EU. 1997-97714-HS-1009)

From 2nd left to 2nd right: Mr Jacques DELORS, President of the European Commission; Mr Helmut KOHL, German Federal Chancellor; Mr Hans Dietrich GENSCHER, German Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs.

© Photographic Archive of the Council of the EU. 1988-72029-1039

“Fiscal rules are non-transparent, pro-cyclical, and divisive, and have not been very effective in reducing public debts. The flaws in the Euro area’s fiscal architecture have overburdened the ECB and increasingly given rise to political tensions”.

Complex and intransparent framework:

Article 126 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, or TFEU.

Regulation (EC) No 1466/97 established the preventive arm of the SGP

Regulation (EC) No 1467/97 established the corrective arm of the Pact

Stability and Growth Pact reform in 2005

Regulation (EC) No 1055/2005 amending the preventive arm

Regulation (EC) No 1056/2005 amending the corrective arm

Euro crisis, the ‘Six-Pack’, the TSCG and the ‘Two-Pack’ (2011-2013)

Regulation (EU) No 1175/2011 tightened the preventive arm

Regulation (EU) 1177/2011 amending the SGP’s corrective arm

Treaty on Stability, Convergence and Governance

“Two-Pack”: Regulation (EU) No 473/2013

“Two-pack”: Regulation (EU) No 472/2013

The Vade Mecum on the Stability and Growth Pact is a manual prepared by the European Commission

Pro-cyclical character

“They constrained the actions of governments during crises and overburdened monetary policy”

Sanctions were not credible (therefore not really binding in good times)

Maastricht thresholds – relatively arbitrary

Low equilibrium interest rates (Hansen 1939, Summers 2014)

r < g environment (and here to stay, Blanchard 2019 argument)

More fiscal space – countries can run higher fiscal deficits and can sustain their debt ratios or even decrease even when having a deficit

High indebtedness after COVID19, but debt service costs historically low

Older OCA theory – Kenen (1969) and Mundell (1961)

Fiscal integration is critical to a well-functioning currency union:

“It is a chief function of fiscal policy, using both sides of the budget, to offset or compensate for regional differences, whether in earned income or in unemployment rates. The large-scale transfer payments built into fiscal systems are interregional, not just interpersonal […]” Kenen (1969).

Farhi and Werning 2017:

„We show that even if financial markets are complete, privately optimal risk sharing is constrained inefficient. A role emerges for government intervention in risk sharing both to guarantee its existence and to influence its operation. The constrained efficient risk sharing arrangement can be implemented by contingent transfers within a fiscal union. We find that the benefits of such a fiscal union are larger, the more asymmetric the shocks affecting the members of the currency union, the more persistent these shocks, and the less open the member economies” (Farhi & Werning 2017).